Some people assume that design patents are similar to utility patents. However, a closer look will show that they are actually quite different. Intellectual property (IP) practitioners—and their clients—who treat design patent applications the same as utility patent applications will often make mistakes and create problems for their IP strategy.

Following are five measures you can take when preparing and prosecuting a design patent to improve the odds that the patent application will hold up under examination (and litigation).

Prior Art Searches

Many applicants struggle with the issue of whether or not to conduct a prior art search prior to filing a design patent application. There are some drawbacks associated with doing so.

First and foremost, a prior art search can increase both the time and expense associated with filing a patent application. In addition, a prior art search can raise duty of disclosure issues and may even put the applicant “on notice” with respect to a competitor’s patent that is uncovered during the search, so that the applicant becomes susceptible to a charge of willful infringement of the patent.

Due to these drawbacks, and the fact that the USPTO does not require a prior art search, it may be tempting to simply rely on the search by the USPTO as part of their examination process.

Generally, though, if you want a design patent that can stand up against litigation, there are good reasons why you should perform a prior art search before filing a patent application.

First, by identifying the prior art before preparing the application, an attorney can avoid making overly broad claims that must later be narrowed to overcome prior art that is revealed during an examination (such narrowing amendments to achieve patentability lead to a presumption that the scope of the claim has been surrendered under the doctrine of equivalents).

Second, if prior art is identified and reported to the USPTO, it will be difficult for someone to use that art to support an invalidity defense.

History is full of cases where a minor claim element caused death of a patent, and a look at these lawsuits pinpoints the little scope of flexibility that exists in claim construction. – Shelza Gupta

Identification of the Invention (Claim)

The first task in drafting a patent application is to identify the invention. This involves:

1. Summarizing only the necessary (critical) features which alone or in combination form a particular visual effect (design)

There are two important reasons for this.

- First, the claims should be as broad as possible; the broadest claim is restricted by the fewest features.

- Second, after the critical features and their effects have been identified, it is important to ask how else these effects can be achieved: i.e., can the same end result be achieved if these features are altered? This is important not only when drafting the claims, which must be broad enough to cover these alternatives, but also in the description of the invention, which must include details of the alternatives so that the broad claims can be supported.

Note: Shading and color-hatching in drawings act as a claim limitation, which limits the scope of the claim when deciding upon both infringement and validity.

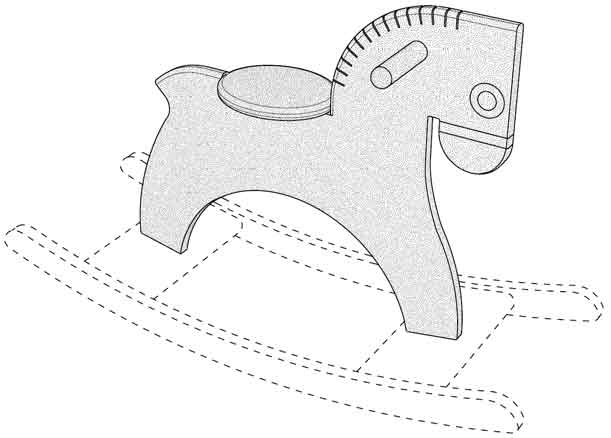

2. Disclaiming unnecessary elements

There are two important reasons for why you would want to disclaim unnecessary elements.

- First, unnecessary elements in design patent drawings require unnecessary drawing effort (and cost) and open the door to drawing errors, examiner rejection and the need to show more drawing views to fully disclose each of the unnecessary claimed features (adding time and cost to the prosecution).

- Second, unnecessary elements in design patent drawings provide unnecessary noninfringement positions. If the alleged infringing product does not include a feature depicted in the design patent drawing, a court may find that there is no infringement.

Note: The selection of what sections should be placed in broken-line borders and what design details should be drawn in broken lines is a matter of informed judgment. Decisions should be made only after there is a complete understanding of the nature of the design and its proposed commercial embodiments, the prior art has been reviewed and analyzed, and the direction of potential future designs around attempted infringements has been carefully considered.

When the alleged infringing product does not include a feature depicted in the design patent drawing a court may find that there is no infringement. Elmer v. ICC Fabricating, Inc.,67 F.3d 1571, 1577 (Fed. Cir. 1990) (Analogous to the “all elements” rule in utility patents)

3. Deleting and/or simplifying superfluous details

Another way to free the drawing from unnecessary elements is to remove them completely and/or to simplify their appearance; for example, hardware and other small parts can be removed from the drawing and the claimed junction is simplified once the hardware is removed (setting forth the best mode contemplated). Another example would be to simplify disclaimed elements to avoid having small dashed lines printed as solid lines and not being clearly distinguished from solid lines.

4. Making sure that the application refer to just one invention, or to a group of inventions that reflect a single inventive concept

This requirement is particularly important when the claim is being drafted to avoid restrictions and there is a risk of disclaiming to the public the restricted-out subject matter. At this stage, the attorney should anticipate and completely disclose all of the possible claim variations that they might have to use during prosecution.

Identification of the Figures (Views)

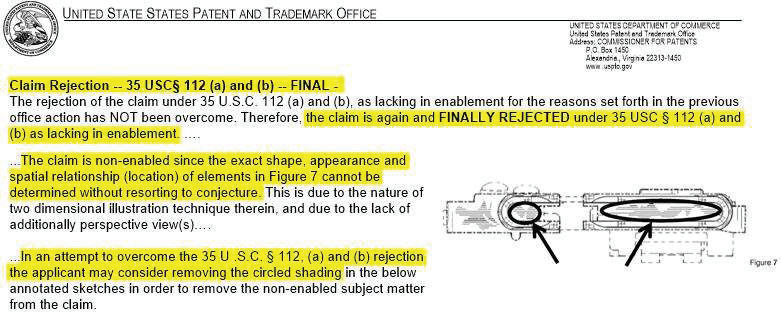

When a surface or portion of an article is disclosed in solid lines, it is considered to be part of the claimed design, and its shape and appearance must be shown both clearly and accurately. Every claimed design feature, no matter how small or hard to see, must be disclosed. This is why particular attention should be paid to making sure that hard-to reach areas of the claimed design (such as holes, openings, depressions, small parts, complex surfaces,.. etc.) are properly disclosed with a sufficient number of collaborating views and proper shading.

If you expect that the examiner may say, “I will approve the application if details A, B, and C are removed/added/dashed-out/converted to solid lines/shaded differently….,” it may be advantageous to include proper drawings in an appendix (to allow for amending the claim as long as the specifications do not change).

In some cases, it may be possible, during prosecution, to change solid lines to broken lines, as long as this change is supported by a written description – i.e., by the drawings and the claim. Such changes can be made for several reasons. For example, to save money, you might file drawings in which all of the important features of the design are shown in solid lines. After the initial embodiment has been allowed and after enough time has passed to confirm that the design has value, you can then broaden the claim by showing some features of the claimed design in dashed lines. This is why using “inverse drawing” (what was a solid line becomes a dashed line, and vice versa) in an appendix is important if you anticipate amending solid lines to broken lines.

It may also be possible to amend broken lines to solid lines (provided there is proper support) – e.g., in response to a prior art-based rejection, the scope of a claim can be changed by claiming “more.” This is why the use of a complete drawing in solid lines (or a photograph) in an appendix is important if you anticipate amending broken lines to solid lines.

Planning for Foreign Filings (and Other Major Drawing Changes)

It is very important to plan for all major drawing changes, not only for foreign filing, but also for foreseen changes in domestic filing. Without good planning, changes to drawings can result in a nightmare due to increased stress, cost and time. However, if changes are planned even before the initial drawing begins, they can be painlessly incorporated at a later date.

- Do you plan to make any changes to the drawings? By deleting features? Adding features? Modifying features?

- Will this application be followed by another application – if so, which one? What changes will need to be planned/accounted for?

- Do you plan to file a design patent in a country that does not accept shading or dashed lines?

Obtaining Sufficient Patent Drawings

Since the design claim primarily consists of drawings, high-quality drawings are essential. The drawings should be clear, accurate, and include all the views needed to sufficiently show the design at the time of filing. In utility patent applications, amendments are commonly part of the prosecution process. In contrast, it may be difficult to amend design applications. If you wish to prosecute a design patent application, you should have access to a skilled draftsperson and be very careful when filing drawings to ensure that they are not altered during the application process.

The most common drawing error is the failure to accurately depict the exact appearance of all claimed design features. If any part of the design is left to conjecture or multiple interpretations, then the claim can be considered indefinite and not enabled. The exact shape, depth, contour, and spatial relationships of all design elements and details, no matter how minor, must be shown clearly and consistently. Design features that often cause definiteness and enablement problems include holes, depressions and indentations, raised areas, open and hollow areas, transparent surfaces, complex curves and bends, small design elements, and internal structures that can be viewed.

Recommended Webinars

Delve deeper into the topics discussed in this article by attending our webinars. These sessions provide further insights and offer the chance to interact with experts in design patent drafting and illustration.

- Design Webinars: Avoiding Non-Correctable Errors in Design Patents:: Discover how to avoid non-correctable errors in design patents and ensure the success of your applications in this informative webinar by IP DaVinci.

- Design Webinars: Handling Advanced Scenarios in Design Patents: Explore strategies for handling advanced scenarios in design patents in this insightful webinar by IP DaVinci, enhancing your ability to navigate complex cases.

- Design Webinars: Cost and Time Saving Tips for Design Patent Drawings: Learn cost and time-saving tips for design patent drawings in this practical webinar by IP DaVinci, aimed at streamlining your patent application process.

Provide Feedback

We value your feedback! Let us know how we can improve or what topics you’d like to see next.

Connect with Mike

Have questions or need support? Connect with Mike for personalized assistance.

Share Your Experience

Found our series helpful? Share it with your network and help others benefit too!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.